Burnt Forest Elder Cries Foul After Court Declares His Land Purchase Null and Void

“The government took my land, built a fire station and now a medical training college on it. The court has cancelled my ownership without awarding me a single shilling. I am pleading with my MP to help me,”

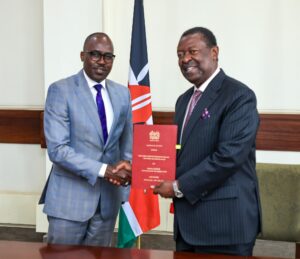

Mr. Francis Seratei, 84, a resident of Burnt Forest, addresses the media outside KMTC Burnt Forest campus, displaying documents he says prove his legal ownership of the disputed land. He is appealing for compensation after the court nullified his ownership and ordered his eviction

An 84-year-old man from Burnt Forest, Uasin Gishu County, is seeking justice after the Environment and Land Court in Eldoret nullified his ownership of a parcel of land he says he legally purchased nearly five decades ago.

Mr. Francis Seratei Moses, a farmer, says he has been left devastated after the court ruled that his purchase of Burnt Forest Township Plot No. 100 was invalid, cancelled his certificate of outright purchase, and ordered his eviction—despite earlier documentation affirming that he had paid for the land in full.

Court Judgment

In a ruling delivered virtually on 13 December 2023, Justice J.M. Onyango declared that:

-

“The purchase over the land parcel known as Burnt Forest Township Plot No. 100 in favour of the Plaintiff is null and void.”

-

The Certificate of Outright Purchase issued in Mr. Seratei’s name was cancelled.

-

An eviction order was issued against him, giving 60 days for him, his agents, and servants to vacate the land.

-

All earlier injunctions were vacated, with the court directing that each party bear their own costs.

The court further explained that the land had long been surrendered by the Settlement Fund Trustees (SFT) to the then Wareng County Council for public use.

“What is apparent is that the Settlement Fund Trustee failed or neglected to document the surrender of the suit property to Wareng County Council and continued to deal with it as if it still belonged to the Settlement Fund Trustee, hence the allocation of the same to the Plaintiff,” the judgment read in part.

The court accepted testimony from DW2, the Assistant Director of Land Adjudication and Settlement in Uasin Gishu, who stated that by October 12, 1970, when the Part Development Plan was approved, the SFT no longer had jurisdiction over the land.

Justice Onyango also noted that the Certificate of Outright Purchase relied on by Mr. Seratei referred to Burnt Forest Settlement Scheme Plot No. 100, which is distinct from Burnt Forest Township Plot No. 100, the property under dispute.

Citing precedents, including Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission v Frann Investments Limited & 6 Others (2020) eKLR, the judge ruled that once land is set aside for public purposes, it remains government land and cannot be alienated for private ownership.

A Lifetime of Documents

Outside the Kenya Medical Training College (KMTC) Burnt Forest campus, which now stands on the contested land, Mr. Seratei clutched a worn-out bundle of official documents he has preserved since the 1970s.

“I paid for this land, I was issued receipts, letters, and even a certificate of outright purchase. Yet the court has now thrown me out without compensation. This is injustice,” he said, his military bearing still visible despite age and frustration.

Documents reviewed by HubzMedia show that:

-

In January 1975, the Settlement Fund Trustees allocated him the land, demanding KSh 2,700, which he paid on February 3, 1975. Receipt No. K401889 was issued as proof of payment.

-

On March 14, 2002, the Ministry of Lands issued him a Certificate of Outright Purchase, confirming him as the allottee of Plot No. 100 after full payment.

-

In July 1999, the then Commissioner of Lands, F.M. Mutie, wrote to the Uasin Gishu District Commissioner confirming that the land “was not public utility” and recommending issuance of a title deed to Mr. Seratei.

Despite this paper trail, the court found that the land had already been set aside for public use, making his acquisition invalid.

From Court Relief to Court Defeat

Mr. Seratei first moved to court in 2012, filing ELC Case No. 374 of 2012 after the Uasin Gishu County Government began construction on the disputed parcel.

In April 2019, Justice Antony Ombwayo ordered that the status quo be maintained and no further construction should proceed until the case was determined. But the final judgment in December 2023 overturned that reprieve, ruling in favour of public ownership.

A Plea for Compensation

Mr. Seratei is now appealing for political intervention, urging Ainabkoi Member of Parliament Samuel Chepkong’a to raise the matter in Parliament and push for compensation.

“The government took my land, built a fire station and now a medical training college on it. The court has cancelled my ownership without awarding me a single shilling. I am pleading with my MP to help me,” he said.

Rights Group Weighs In

The case has now attracted the attention of human rights advocates.

Kimutai Kirui, of the Centre Against Torture, has called on Ainabkoi MP Samuel Chepkong’a to step in and ensure that Mr. Seratei is compensated for the land he bought in good faith.

“It is shocking that the court could establish the fact that the old man legitimately purchased the land, yet fail to order compensation,” Kirui said. “The government has built a college on his land, and justice demands that he be paid for his loss.”

Wider Implications

Land disputes like Mr. Seratei’s are common in Kenya, where settlement schemes, township allocations, and public utility reserves often overlap, leaving citizens entangled in legal uncertainty.

Legal experts argue that while courts rightly protect public land, the state must also protect citizens who invested money in good faith.

“This case underscores the need for a national compensation policy for historical land injustices. People like Seratei should not be left to carry the burden of government’s administrative failures,” Kirui added.

For Mr. Seratei, the court’s decision marks the culmination of a painful legal journey spanning over a decade. Though the documents he holds suggest ownership, the judgment has effectively erased his claim.

“I bought my land legally, and now I am being thrown out like I never existed,” he told reporters, his voice breaking.

As he awaits a political or legal lifeline, his case shines a spotlight on the unresolved land injustices that continue to haunt many Kenyans, decades after independence.